Blog

COVID-19 intensifies global need to support informal workers in their struggle

Three guiding principles for a better deal

The world is facing an existential crisis that poses challenging questions: whether to put people and nature before owners of capital and technology; whether to protect the rights of the disadvantaged or the interests of the elite. This is a defining moment to follow the call for racial and economic justice and change structures of discrimination and disadvantage.

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed pre-existing fault lines — inequities and injustices — at the base of the economic pyramid and shown a spotlight on the contributions of frontline workers, many of whom are informally employed. Informal workers represent 61% of all workers globally — a total of 2 billion workers worldwide. Of these, an estimated 1.6 billion (80%) could see their livelihoods destroyed due to the lockdowns in response to COVID-19.

But long before COVID-19, informal workers have been struggling for justice, equality, and dignity. The current COVID crisis — both the pandemic itself and the policy response to it — exposes the injustices, inequities, and indignities informal workers face. It is time to support them in their struggle.

Most workers globally are informally employed and struggle against discrimination

Most informal workers are trying to earn an honest living without social or legal protections, basic infrastructure, transport and social services, access to public space or public procurement bids, financial or business development services, and without tax breaks and other incentives. Informal workers navigate these deficits in the face of systemic discrimination and violence by local authorities and the police, as well as stigmatization and neglect by planners and policy makers.

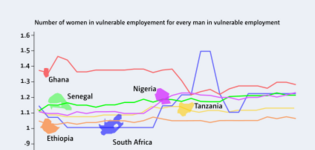

The stigmatization and penalization of these workers is due to what they do (their work is seen as illegal or non-productive) and to who they are: as many informal workers are migrants or are from disadvantaged racial, ethnic or caste groups, or from religious ‘minorities’. Also, in many countries, especially developing countries, a higher percentage of women workers than men workers are informally employed.

Despite their crucial contributions, the state is often overtly hostile to these workers.

Despite their crucial contributions, the state is often overtly hostile to these workers. To cite just one of too many examples, street vendors around the world must navigate daily harassment and bribes, routine confiscation of their goods, and frequent evictions by police and local authorities to earn a livelihood. Far too often policy makers and government officials are men from dominant race, ethnic, or caste communities who view informal workers, their struggle to survive and the injustices, inequities, and indignities they face, as somehow reflecting the ‘natural order of things’, without recognizing, much less addressing, the historic racism and sexism inherent in how informal workers are perceived and treated.

Systemic racism is clearly a central critical driver of social and economic injustice. But in everyday individual lives, race intersects with other sources of systemic discrimination and disadvantage — including sexism and gender norms, as well as citizenship and resident or migrant status.

Consider the intersection of caste and patriarchy in modern India. The caste hierarchy in India has persisted over millennia, providing a uniquely oppressive framework of hierarchy and discrimination that is supposedly defined by occupation and preserved by endogamy. Caste and gender norms intersect to determine what is considered proper behaviour and work for women from different caste groups. Furthermore, notions of purity and pollution, associated with different tasks, and the castes that perform them, continue to shape labour markets, including the type of work people do.

Around the world, the COVID-19 crisis is being used by states as a pretext to double down on, rather than remedy, these existing forms of discrimination, including through evictions from and destruction of places of work, and incidents of police brutality towards workers attempting to continue to work to feed their families.

Around the world, the COVID-19 crisis is being used by states as a pretext to double down on, rather than remedy, these existing forms of discrimination ...

The COVID-19 crisis reveals deeper problems

During the first month of the crisis, informal workers globally experienced a 60% drop in income — more than an 80% decline in Africa and the Americas, 70% in Europe and Central Asia, and 22% in Asia and the Pacific. Informal workers have responded around the world with a common lament or plea: We will die of hunger before we die from the virus.

People have come to appreciate frontline health workers — clapping or singing to honour them, calling them everyday heroes. The frontline workers in the food system have received less, but increasing, appreciation. These include the farmers and agricultural day labourers, processing plant workers, warehouse and delivery workers, wholesale food market workers, grocery workers, restaurant workers and street vendors. But the fact that most of these workers are informal and do not enjoy essential worker rights or social protection is not well understood.

The pandemic and the lockdowns have exposed the central weaknesses and inequities of our systems for the production and delivery of essential goods and services — notably health and food systems — including how the people who provide them are undervalued and underprotected. The fact that these systems are neither equal nor resilient presents a wakeup call.

Consider the global food system. According to the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), ‘COVID-19 has laid bare the underlying risks, fragilities, and inequities in global food systems, and pushed them close to breaking point. Our food systems have been sitting on a knife-edge for decades: children have been one school meal away from hunger; countries — one export ban away from food shortages; farms — one travel ban away from critical labour shortages; and families … one missed day-wage away from food insecurity …’.

A better deal for informal workers

The COVID-19 crisis has exposed that economic injustice and inequality persist around the world, in developed, emerging, and developing economies. Most specifically, it has exposed that most of those who provide essential goods and services do not enjoy essential rights. As long as informal workers, the majority of all workers globally, are stigmatized, penalized, and criminalized for what they do and who they are, they cannot work their way out of poverty.

A better deal for informal workers will require: redistributing wealth through appropriate tax policies; investments in strengthening local systems of production and consumption; ensuring universal access to good quality public services, especially care services, with well-remunerated workers; regulating markets to limit the power of capitalists to over-exploit nature and undermine human rights; ending state violence, and challenging the dominant narrative that stigmatizes informal workers as a problem rather than recognizing their contributions in providing essential goods and services.

The global community should honour the guiding principles that informal worker organizations are calling for.

Since long before COVID-19, informal workers have been organizing, negotiating, bargaining and joining hands to make their demands known, often across lines of caste, race, ethnicity, religion, and gender.

The global community should honour the guiding principles that informal worker organizations are calling for:

# 1 – Do no harm

Local governments and the police should refrain from harassing, bribing, evicting, and otherwise penalizing the working poor, which are standard practices in normal times. They should not use the crisis or public health concerns as an excuse to demolish homes and workplaces of the poor. Police should facilitate the safe passage of migrant workers to their village homes, rather than blocking or beating them along the way.

# 2 – Nothing for us without us

Membership-based organizations of the working poor in the informal economy and other membership-based organizations of the poor should be invited to advise on or partner with relief, recovery, or reform efforts. They have the ground-level knowledge and experience to ensure that relief efforts are targeted to and appropriate for the poor, including the working poor, and to assist in channeling the targeted resources to the poor.

# 3 – Envision a transformation

Finally, and most fundamentally, there is a need to envision a transformation: a paradigm shift. There is a need for a new model of work and production, equitable and redistributive, that recognizes and values all forms of work. The transformation required to achieve that model must begin now, with a commitment to recovery plans that focus on the base, not just the tip, of the economic pyramid. Long-term investments are needed to rebuild economies around the understanding that informal economy workers, especially women, sustain households, communities, and economies; are central to the rebuilding of supply chains; and require a guarantee of decent work standards in all sectors.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network