Blog

Five lessons from Martin Ravallion’s WIDER Annual Lecture

Direct interventions against poverty in poor places

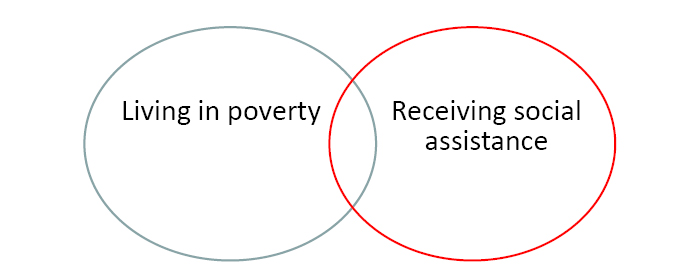

On 23 March researchers, policy makers, and politicians gathered at the Stockholm School of Economics (or joined online via the webcast) to hear Professor Martin Ravallion deliver WIDER Annual Lecture 20 and discuss its implications. Held in collaboration with the Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics (SITE) this year’s lecture focused on poverty, and the evaluation of the social assistance programmes aimed at tackling it. There are one billion people in the developing world in receipt of some form of social assistance, and one billion people living in poverty. However, these are unfortunately mostly not the same people.

In particular Ravallion focused on the potential trade-off between social protection, providing short-term support to ensure no one falls below some crucial level, and promoting people out of poverty by permitting a sufficiently large wealth gain to put them on a path to a sustained increase in their level of wealth. This blog post outlines five of the many takeaways from Professor Ravallion’s excellent lecture.

1. Growth alone is not enough to end poverty

1. Growth alone is not enough to end poverty

Ravallion began his lecture by pointing out that although economic growth has come with lower absolute poverty, it has had much less impact on relative poverty. While relative inequality is falling in some countries, it is rising in others, and absolute inequality is rising in most growing countries.

Ravallion suggests that the very poorest are being left behind, shut-out from the benefits of growth. Furthermore, while the livelihoods of many have been improved, economic shocks could cause people to fall back into poverty if there are no adequate social protection policies in place. Social assistance policies are one way in which this dynamic is being challenged

2. The cruel irony of poverty reduction is that poorer countries are less effective in reaching their poor

During his lecture Ravallion highlighted the fact that compared to today’s poor countries, today’s rich countries appear to have done better at reaching their poorest during their earlier stages of development. Some poor countries do better than others when it comes to reaching the poorest, and the state’s capacity to reach the intended recipients of social assistance schemes should be taken into account when designing social assistance programmes.

During his lecture Ravallion highlighted the fact that compared to today’s poor countries, today’s rich countries appear to have done better at reaching their poorest during their earlier stages of development. Some poor countries do better than others when it comes to reaching the poorest, and the state’s capacity to reach the intended recipients of social assistance schemes should be taken into account when designing social assistance programmes.

3. Targeting is a fetish that can create poverty traps

In light of the above, Ravallion suggests that an excessive focus on targeting programmes is often misguided. In some instances, he argued, targeting of social programmes itself has become a fetish. There is too much focus on making sure the wrong people don’t receive support, and not enough focus on the bigger problem of making sure that the right people do.

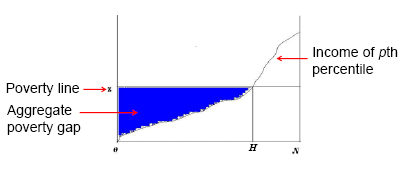

If targeting is taken too far it can even create poverty traps. Transfers that simply aim to bring everyone below the poverty line up to that line would mean that someone starting to earn enough to move out of their poverty would lose their benefits at the same rate as they increase their wages. This would equal a marginal tax rate of 100% for the poorest people, and clearly creates a disincentive to move out of poverty through work.

If targeting is taken too far it can even create poverty traps. Transfers that simply aim to bring everyone below the poverty line up to that line would mean that someone starting to earn enough to move out of their poverty would lose their benefits at the same rate as they increase their wages. This would equal a marginal tax rate of 100% for the poorest people, and clearly creates a disincentive to move out of poverty through work.

For Ravallion the primary focus of social security policy should be to reduce poverty, not to improve targeting.

4. The trade-off between protection and promotion may exist, but it is exaggerated

Policy makers typically want social assistance programmes to assure a minimum standard of living, however this may discourage personal efforts to escape poverty through work. Consequently, Ravallion suggests, it is true that there may be a trade-off between policies that seek to protect people from poverty by providing them with a supplemental income, and those that seek to promote people out of it by encouraging wealth creation. Ravallion argues that while incentives cannot be ignored in policy design the trade-off in practice can be exaggerated.

Ravallion argues that the bulk of the evidence for developed countries does not support the view that there are large work disincentives associated with targeted antipoverty programs. In the short run a fiscal stimulus for the poorest, in the form of a social assistance programme, raises aggregate effective demand, and hence output. In the long-term, in a fully-employed economy the idea of a tradeoff can also be questioned as protection from large negative shocks may be crucial for sustained promotion.

5. Improving the protection-promotion trade-off should be a focus

5. Improving the protection-promotion trade-off should be a focus

Given the above, Ravallion argued, the focus for policy makers seeking to reduce poverty should be on designing programmes that adequately navigate the potential tradeoff. There are a number of ways that incentives for promotion can be built into social protection. One way this can be done is through making the receipt of social assistance conditional on fulfilling a requirement that has the potential to aid in promoting people out of poverty. Ravallion points out that over 30 developing countries already use programmes that, for example, impose a condition that children of the recipient family must have adequate school attendance and health care. These kinds of programmes can improve both current incomes and future incomes, through higher investments in child schooling and health care. Early examples of this trend include Food-for-Education Program in Bangladesh; Mexico’s PROGRESA (Oportunidades) and Bolsa Escola in Brazil.

Programmes which require people to undertake some kind of work in order to receive social assistance (workfare), could also help balance the trade-off. When discussing workfare programmes policy makers tend to emphasize protection over promotion. However Ravallion suggests that one direction for reform here would be to assure that workfare is productive—that the assets created are of value to poor people. If this was achieved then workfare programmes could also serve the goals of both protection and promotion.

While there may be great potential in such programmes, Ravallion also highlights some concerns. Strict conditions may cause programmes to become inflexible, sending children to school may in itself be a trade-off if potential earnings are lost as a result, and such programmes may be ineffective if the problem is on the demand side (there are more children in school, but are the schools teaching effectively?).

Social assistance a key issue – for both researchers and policy makers

Social assistance programmes are already a major weapon in the battle against poverty and if we are to successfully meet the targets set by the UN Sustainable Development Goals they will undoubtedly have to play a crucial role. As such this lecture provides a timely insight into what we have learnt from observing social assistance programmes so far, and, with its emphasis on the protection-promotion trade-off, highlights the challenges such programmes still face.

This blog post only scratches the surface of the wealth of knowledge that was imparted by Ravallion during his WIDER Annual Lecture, and there are many ways in which you can dig deeper. Watch the full lecture on YouTube, follow the conversation on Twitter with #AL20, review Ravallion’s slides on our website, and stay tuned for the publication of this lecture, which will be announced on the WIDERAngle blog. Visit our publications search for a wealth of research on social assistance, and keep an eye on our project ‘The economics and politics of taxation, and social protection’ (#Tax4Protection) and our ‘Social Assistance, Politics, and Institutions’ (SAPI) database. You should also be sure to read Martin Ravallion's new book on this topic "The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement, and Policy".

This blog post only scratches the surface of the wealth of knowledge that was imparted by Ravallion during his WIDER Annual Lecture, and there are many ways in which you can dig deeper. Watch the full lecture on YouTube, follow the conversation on Twitter with #AL20, review Ravallion’s slides on our website, and stay tuned for the publication of this lecture, which will be announced on the WIDERAngle blog. Visit our publications search for a wealth of research on social assistance, and keep an eye on our project ‘The economics and politics of taxation, and social protection’ (#Tax4Protection) and our ‘Social Assistance, Politics, and Institutions’ (SAPI) database. You should also be sure to read Martin Ravallion's new book on this topic "The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement, and Policy".

Follow us on twitter @UNUWIDER. Follow James Stewart on twitter @deveconwatcher.

Join the network

Join the network