Blog

An economist’s view on migration and refugees

Few issues have been so contentious in recent years as international migration. The refugee crisis sparked not least by the Syrian war has shown that policies governing migration are in a tangle. To quote Jeffrey Sachs’ recent article (2016): ‘There is no international regime that establishes standards and principles for national migration policies, other than in the case of refugees’. To add to the tangle, many issues are often bundled up together in the public debate, and it can be difficult to disentangle the various elements in the mix. This is not helpful from a policy perspective. Uncovering some of the key facts on international migrations — both voluntary and forced — can help us understand the issues currently at hand. From an economist’s perspective, it is important to distinguish between root causes of migration as well as consider the positive effects of migrants on local economies.

Some facts on international migration and refugees

According to most recent UN DESA Population Division projections international migration is likely to increase in the coming years, and has done so for decades. Therefore, a serious debate on migration is now more topical than ever. Demographic trends in Europe and sub-Saharan Africa diverge to such an extent that the push-and-pull of migration will intensify as the population of Europe gets older while that of Africa younger. In the midst of all this, it is important to keep in mind some basic facts that often get trampled in the heated debate on refugees (see World Bank Development Indicators and UNHCR relevant data).

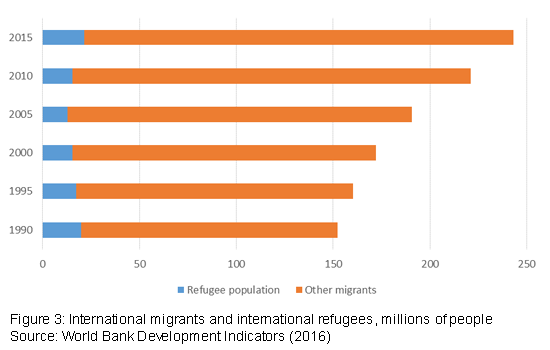

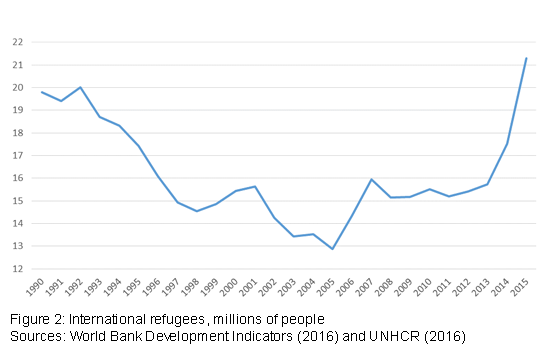

The majority of international migrants are not forcibly displaced. In 2015, approximately 9% cent (or 21.3 million) of all international migrants were international refugees; this number is only slightly higher today than in 1990. Furthermore, of the 65.3 million people displaced from their homes, most — 40.8 million— are displaced within their own country.

Most international migration occurs between countries within the same major area. For example, the volume of South-South migration is higher than South-North migration. Also, most migrants originate from middle-income countries and reside in high-income countries.

Even though most international migrants reside in the developed world, most refugees (nearly 90%) are hosted by middle-income countries. In 2015, over half (54%) of international refugees were from Syria, Afghanistan, or Somalia; and the main contributing factor to the increase of refugees between 2010 and 2015 was the war in Syria. Excluding Syria, the increase from the end of 2011 to mid-2015 would have been only half a million refugees.

Thinking clearly about the root causes of international migration

Economists will typically think of migration in terms of push-and-pull factors as illustrated in the Harris-Todaro model of rural–urban migration). However, it is not sufficient to talk about root causes and there is a need to distinguish between forced versus voluntary (or economic) migration — in addition to differences between internal versus international migration.

A useful approach in the case of forced migration for identifying root causes is to distinguish between (see Angenendt et al. 2016):

- Structural causes of displacement, comprising a broad range of negative political, economic, and social developments; and

- Acute causes of displacement which can be armed conflicts, civil wars, and other forms of generalized violence.

This distinction is important if we want to address the issue in the country of origin and prevent forced migration and crises.

Economic benefits of migration

Once people are forced to flee their homes to avoid persecution or war, they need international protection and new places to settle. Typically economists see migration as largely positive for the economy and the individual — the movement of people into higher-productivity sectors that pay more. These distributional effects are, nonetheless, complicated as illustrated by Sachs (2016). Migration can cause winners and losers, and public judgment is mixed.

Part of this issue is what economists refer to as the ‘lump of labour’ fallacy, which suggests that there is a fixed number of jobs to share around. Low-skilled nationals may perceive migrants as taking ‘their’ jobs, but the evidence shows that this effect is actually quite weak. According to economic research, migrants add to purchasing power in an economy, which creates more work including for low-skilled nationals.

Therefore, also refugees could better contribute to the host economy if they are provided access to job markets more quickly than they currently are in many host countries. Experience has also shown that people who arrive in a developed country as a refugee — and there receive education — can later contribute to the rebuilding of their crisis-stricken home country with skills that they would not have otherwise obtained. This education can also be regarded as a form of aid that contributes to the long-term post-crisis development of the countries of origin.

In the view of an economist, migrants — whether they arrived as economic migrants or refugees — are a potential source of valuable labour that benefits a host society. In the second part of this blog we will discuss how the international community should respond to migration and refugees.

UNU-WIDER’s ‘Responding to Crises’ conference, held on 23-24 September in Helsinki, will improve knowledge about continuing, unexpected, and future crises. It will also serve as a forum to discuss the options available for governments, international agencies, NGOs, civil society and private citizens to respond.

Join the network

Join the network