Policy Brief

WIDER Annual Lecture Brief | Informality: the Achilles Heel of social protection in Latin America

Making a case for universal social protection in Latin America

The 2019 WIDER Annual Lecture discusses the challenges of social protection in economies with large informal sectors, such as in Latin America. Making a critical distinction between social insurance and social assistance programmes — the former address risks which are common to all workers (illness, disability, death, longevity); the latter focus on redistribution, which in turn focuses on a subset of the population, typically those living in poverty.

The current social protection combination (CSI and NCSI) is bad economic and social policy because workers transit from formal to informal jobs and vice versa, and often workers consider the benefits of contributory programs are not worth their cost, while free NCSI benefits subsidize informal employment As a result of the combined system, too many resources are shifted towards the informal sector

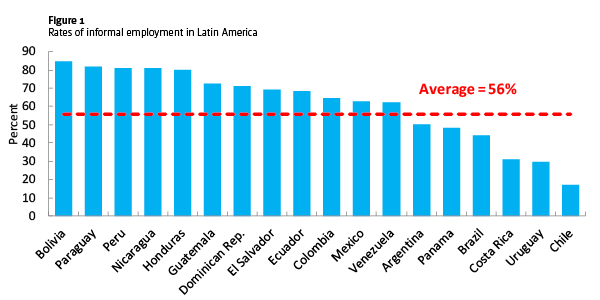

The social protection system plays a significant role in contributing to Latin America’s large informal sector — a large informal sector points to a failure of public policy

Social protection plays a fundamental role in tackling poverty and inequality.

In adopting the Bismarckian model for social insurance — where insurance for salaried workers is financed through wage-based contributions, referred to as contributory social insurance (CSI) — Latin America restricted coverage to formal workers, those with salaried jobs in firms that comply with the law. Coverage usually includes health, disability, life insurance, and retirement pensions; and at times can include also daycare, child allowances, and housing subsidies. Unemployment insurance is rare and is replaced by strong restrictions against dismissal and onerous severance pay.

Later on, Latin America created a separate social insurance system for informal workers, which includes those who are self-employed or work for small family businesses. Referred to as non-contributory social insurance (NCSI), it is financed from the general budget. NCSI programmes are unbundled — they mostly focus on health and pensions, but in some countries they also include daycare, child allowances, and so on. The result is that access to effective social insurance is determined by a worker’s status in the labour market.

The cracks in the CSI–NCSI combination model

The cracks in the CSI–NCSI combination model

The CSI–NCSI combination demonstrates bad economic and social policy for two key reasons. First, during their lifetime workers move from formal to informal jobs and vice versa, which means that at times they are protected by CSI programmes, and at times by NCSI programmes. This is a problem, because typically CSI health and pension benefits are better than NCSI benefits. Second, often workers consider that CSI benefits — which are paid for via a wage tax — are not worth their cost. Thus firms and workers try to evade the tax, but in order to avoid detection and fines, firms remain small and are less productive.

Countries in Latin America began to offer NCSI to informal workers after what economists call the ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s — almost 80% of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean experienced reductions in their GDP levels (Lüders, 1991). From a social point of view, NCSI programmes are welcome and are often associated with investments in human capital. However, increasing the benefits of NCSI programmes does not present a good solution as it can worsen the equity–efficiency trade-off, and permanently lock poor workers in informal low-productivity employment.

From an economic point of view, NCSI programmes subsidize informal employment — informal workers get benefits that neither they, nor the firms they are associated with, pay for — and they subsidize evasion, as illegally hired salaried workers usually receive NCSI benefits.

From an economic point of view, NCSI programmes subsidize informal employment — informal workers get benefits that neither they, nor the firms they are associated with, pay for — and they subsidize evasion, as illegally hired salaried workers usually receive NCSI benefits.

In Mexico for example — where 57% of the labour force is informal — a typical business is made up of a few members of an extended family who do not receive a contractual salary. If business is booming the family may decide to hire outside workers, increasing its risk and costs. Enrolling its employees in CSI would add 30% or more to its labour costs, and if business plummets, by law salaried workers cannot be fired without a ‘just’ cause (summary of IDB paper featured in The Economist, 2018).

As a result of the CSI–NCSI system too many resources are shifted towards the informal sector — the subsidy to informal employment adds to the tax on formal employment. The marginal revenue product of resources in the formal sector is higher than in the informal one. This lowers Total Factor Productivity (TFP) and punishes growth through many channels: suppressed firm growth; underexploited economies of scale; reduced investments in training; less on-the-job learning. Since informal firms are less intensive in skilled labour, its demand is depressed. Together, they play a significant role in contributing to Latin America’s large informal sector.

Policy makers need a new model for social protection

Policy makers need to find other sources of taxation other than taxes on wages to fund social insurance

The current system should be traded for universal social insurance

Universal social insurance will facilitate business growth, increase investments in training, and lead to more productive job opportunities for all

Latin America’s large informal sector points to a failure of public policy. To reduce informality, countries in Latin America must shift towards universal social insurance — risks that are common to all workers should be funded from the same source of revenues, and access to quality social insurance should be delinked from workers’ status in the labour market making it possible for everyone to be covered. To achieve this, policy makers need to find alternative sources of taxation other than taxes on wages — a complex fiscal challenge.

Trading the CSI–NCSI system for universal social insurance is indispensable for social inclusion. But it will also facilitate business growth, increase investments in training, and lead to more productive job opportunities for all.

Join the network

Join the network