Research Brief

Children’s nutrition status in Mozambique

Determining the impact of rising food prices

Evidence obtained from detailed household surveys in Mozambique during the 2008-09 food price shock reveals just how pronounced the impact of food price inflation can be on children’s overall nutrition status.

Moderate and severe underweight prevalence in children in Mozambique is significantly influenced by food price inflation

High food price inflation during the food price shock of 2008-09 may be responsible for an additional 39,000 moderately underweight and 24,000 severely underweight children in Mozambique

High stunting and wasting levels are more likely a result of extreme shocks and are not as sensitive to monthly price inflation as underweightness

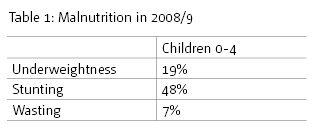

In Mozambique, malnutrition continues to plague poor children even during times of low inflation. However during the shock of 2008-09 when the prices of staple foods increased dramatically the numbers increased dramatically (see Table 1), due to the decrease in the availability of affordable food products.

Mozambique is a net food importer; during periods of high price inflation of food products in international markets—such as those experienced during 2008-09—the wellbeing of the most vulnerable segments of the population is compromised. Imported food items are particularly important to urban households that generally produce no food for self-consumption and are reliant on food from outside Mozambique.

Most rural areas, on the other hand, produce more of their own food themselves but are subject to climate changes that can negatively impact crop output. Unfortunately, climate fluctuations caused a less than optimal harvest in 2008 and many rural households experienced a food crisis as well. Consequently, the prices of both imported and locally-produced food increased significantly.

Empirically assessing the impact of food price inflation on childhood nutrition

Prior to the food price crisis, average national inflation for food products was nearly 15 per cent, during the food price shock between 2003 and 2006 the inflation average increased to around 32 per cent. In-depth models indicate that, from 2008-09, there were an additional 39,000 moderately underweight children and 24,000 severely underweight children in Mozambique due to food price inflation. These numbers represent 7 per cent and 16 per cent increases, respectively.

In contrast to the negative impact of food prices on underweight ratios, stunting and wasting measures do not appear to have such an explicit link with food price inflation. In fact, analysis indicates that stunting and wasting were virtually unaffected by the food price hikes. This could be due to the fact that stunting and wasting are most often the result of a more extreme shock than price inflation—one which prevents households from providing the minimum nutrition necessary for growing children. Monthly inflation of food prices would, however, likely result in a switch to cheaper foods of lesser nutritional quality, variation and value, explaining the increase in underweight children.

The findings of this analysis of the impacts of food price inflation on children’s nutrition is particularly important as it contributes to mounting evidence that the combination of slow agricultural productivity growth, weather shocks, high real food prices, and high real fuel prices in 2008-09 have discernible and negative impacts on the welfare of households.

Join the network

Join the network