Policy Brief

Aid for governance

How to support effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions for sustainable development?

Aiding government effectiveness in developing countries has been a priority issue for the international donor community since the 1990s. With the Paris Declaration in 1994, donors further committed to aiding government effectiveness in a manner consistent with local ownership and harmonization with national development objectives. These issues have received renewed attention in discussions surrounding the Sustainable Development Goals, which have highlighted the importance of effective governance and institutions.

The fact that countries most in need of assistance are often those where institutions and domestic political will are weakest can pose major challenges for donors committed to locally-owned reforms

Work on governance presents a clear rejection of the ‘one-size-fits-all’ donor-driven governance interventions of the 1980s and 1990s. Context clearly matters

However some initiatives, such as civic education, seem to work similarly across diverse contexts

Aid does not always support better governance, but it has worked in multiple situations and contexts

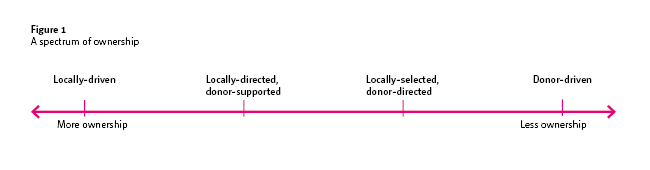

Governance goals and local ownership: inherent tensions

Experience with governance reform illustrates inherent tensions. First, politics plays a central role in governance reforms, not least because local elites may be hesitant to undertake reforms that could undermine the status quo or threaten established interests. Second, countries most in need of reforms are often those where institutions and domestic political will are weakest, which can pose major obstacles to locally-owned reform processes. Still, third, interventions without local ownership go against donor commitments and are likely to be less effective than intended. Given such tensions, operating along different points of the ownership spectrum may be advisable for different types of governance reforms – even as we clearly avoid ‘donor-driven’ approaches.

Context and sequencing

Closely related to issues of ownership is consideration of local context. Recent work on governance presents a clear rejection of the one-size-fits-all donordriven governance interventions of the 1980s and 1990s. Context clearly matters.

Weak and fragile states raise particular contextual challenges for governance reform. Given weaknesses in existing governance institutions, policies and reforms transplanted from elsewhere may operate very differently in these contexts.

For instance, in the case of security sector reform in Sierra Leone, the Inspector General of Police appointed in the late 1990s, did everything by the book, adopting reforms that ‘closely mirrored the recommendations provided by the latest research’, but the fragile context imperiled reform efforts.

For instance, in the case of security sector reform in Sierra Leone, the Inspector General of Police appointed in the late 1990s, did everything by the book, adopting reforms that ‘closely mirrored the recommendations provided by the latest research’, but the fragile context imperiled reform efforts.

Borrowed practices from developed countries also can pose problems in developing countries more generally. For example, value-added taxes (VAT) have been relatively less successful as a source of revenue generation in low-income countries than in developed countries. Among other issues, weak organizational capacity and the absence of reliable written or electronic records of economic transactions upon which to base VAT assessment make it harder to collect, in some instances creating new opportunities for fraud and corruption.

No easy answers

There are no easy answers in terms of how to take context into account. Of course, engaging local knowledge is advisable. Attention to timing and sequencing also are means to adapt efforts to diverse institutional and political environments. Introducing incremental versus comprehensive reform can be an important component of addressing the political context, including pockets of opposition to reform.

Yet, some initiatives seem to work similarly across diverse contexts. Analysis of the impact of civic education programmes in multiple country contexts (Dominican Republic, Poland, South Africa, Kenya, and the DRC), for instance, shows that even across such diverse situations several clear patterns of effects from similar programmes can be documented. We should pay more attention to understanding also when context does not matter.

Transparency and impact evaluation

Finally, we need to develop better ways of evaluating and learning from past experience. Currently, data challenges and a sometimes lack of transparency on the part of donor organizations make this difficult. In the area of civil service reform in particular, international organizations have released very little information about their support of reform efforts, although both governments and civil society should have the opportunity to evaluate such experience.

Even with the best data, impact evaluation of governance reform is challenging because causality is so complex. Uncovering a statistically significant relationship between two variables does not prove that one causes the other. In studying the effect of regulation on economic growth, for instance, it is equally possible for the causal arrow to point the other way, with strong economies lowering regulation and weak economies increasing it.

In unpacking causality claims, considerable attention has been paid in recent years to the use of randomized controlled trials and other experimental methods. These methods have both strengths and limitations, which illustrates the value of a variety of qualitative and quantitative methods and data sources, including surveys, case studies, and interviews.

Different balances between local and donor ownership may be advisable for different types of governance reforms

Introducing incremental versus comprehensive reform can be an important component of addressing the political context, including pockets of opposition to reform

Developing better ways of evaluating and learning from past experience is essential

What’s next?

Many aid skeptics point to corruption in developing countries to conclude that aid contributes to poor governance. Such claims obscure the important fact that governance involves much more than corruption. Aid does not always support better governance, but it has worked in multiple situations and contexts.

In order to improve its record, we need to continue work on each of the points highlighted above. Furthermore, at a time of contracting donor resources, policy makers need better answers from researchers about the best bang for their buck. In other words, future work should also consider which areas of governance should be prioritized for intervention and how these can be reconciled with those governance areas currently ‘owned’ by recipient countries.

Join the network

Join the network