Policy Brief

Distributional effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Zambia

Zambia’s economic growth has been flattening over the past decade. In 2020 economic prospects further worsened, following the onset of the pandemic, rising debt, and the Eurobond default. In this unprecedented scenario, there is the need to examine impacts on welfare and the mitigation role taxes and benefits play. MicroZAMOD, the tax-benefit microsimulation model for Zambia, helps in the investigation of the COVID-19 shock.

The coronavirus pandemic has dealt a severe blow to the Zambian economy in difficult times

The COVID-19 Emergency Cash Transfer stabilized incomes of the most vulnerable households and offset some of the negative shock on poverty

The general tax-benefit system contributed very little to stabilize incomes and only provided some relief for some of the most well-off households

Like in many countries across the globe, the Zambian government imposed containment measures in 2020 seeking to limit the spread of COVID-19. These lockdown measures, together with the rippling effect from the fall in trade and tourism originating from other countries, dealt a major blow to economic activity and people’s incomes.

To alleviate the detrimental effects on vulnerable households the government introduced the COVID-19 Emergency Cash Transfer starting in July 2020 for six months, supplementing the existing Social Cash Transfer programme. Zambia furthermore paused its Home-Grown School. Feeding programme during the lockdown, leaving it to the households to afford the extra meals for their children who would usually have received them at school Other social protection measures included the suspension of custom duties and VAT on additional medical supplies used in the fight against COVID-19 and waiving of tax penalties and interest on tax penalties. Tax-related measures are not included in this analysis due to data limitations.

This policy brief aims to quantify the impacts of government action in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis focuses on 2020, thus on the first nine months of the pandemic. The MicroZAMOD tax-benefit microsimulation model is used to estimate the impact of the pandemic on incomes, poverty and inequality and the role of the general tax-benefit system, as well as discretionary government policy interventions in mitigating the adverse effects of the crisis in Zambia.

Severe blow to GDP growth overall, but not uniform across economic sectors

Severe blow to GDP growth overall, but not uniform across economic sectors

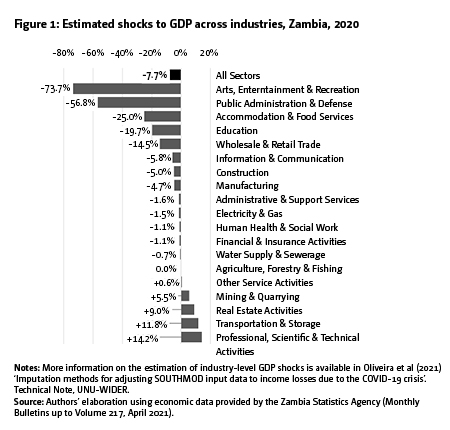

Overall, in 2020 the GDP contracted by 7.7% compared to pre-COVID trend predictions (Figure 1). This finding is based on estimated sectoral shock changes in economic activity compared to a hypothetical situation in the absence of COVID-19 in 2020 by aggregating each industry’s deviation from its pre-pandemic growth trend between 2017–19.

Across industries, the majority experienced negative growth, with the arts, entertainment, and recreation sectors seeing the worst shock (-74%). Out of the four sectors with positive growth, the professional, scientific, and technical activities recorded the most growth (+14%) when compared to the pre-COVID trend prediction. The mining sector, on which the Zambian economy heavily relies, grew by 5.5% despite the crisis mainly due to copper price hikes especially in 2020.

These sectoral shocks were translated to changes in individuals’ incomes in the microlevel survey data used by the MicroZAMOD model.

Poverty and inequality increased but the emergency cash transfer offered some protection to the most vulnerable households

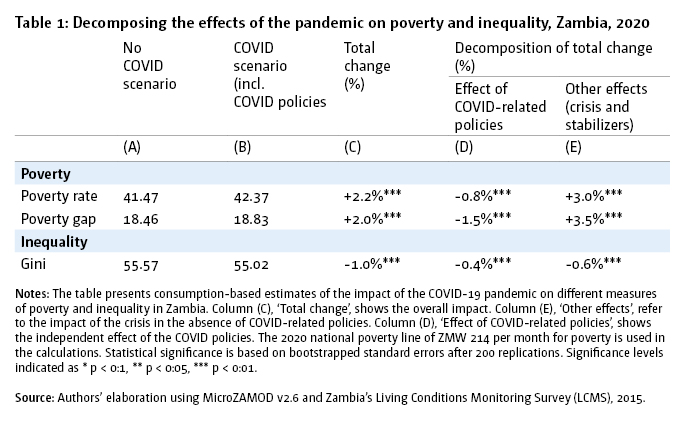

Headcount poverty worsened by 2.2%, the poverty gap by 2%, and inequality as measured by the Gini increased by 1% (Table 1, column C). Without the COVID-response measures, the analysis indicates that the increase in headcount poverty and poverty gap would have been even higher (3% and 3.5% respectively, column E).

The COVID-19 Emergency Cash Transfer was highly effective in cushioning incomes of those in the lower half of the income distribution. While it was well-targeted, the overall expenditure on the benefit is not negligible. Households already receiving the Social Cash Transfer before the crisis (paid at 90 Kwacha per household per month, or 180 Kwacha per month of disabled households) received a top-up of 400 kwacha (US$24.30) per month through the new COVID-19 Emergency Cash Transfer. The additional expansion of the scheme to other target groups was not possible to model, likely leading to an underestimation of the full impact of the programme in the analysis.

In addition, the closing of schools resulted in higher private consumption needs for vulnerable households due to pausing of the Home-Grown School Feeding programme, which is counteracting the positive impact of the COVID-19 Emergency Cash Transfer to some extent. This is assuming that households would feed children the same value of a meal as received at school.

The existing tax-benefit system barely stabilized incomes

Automatic stabilizers — i.e., the automatic response of tax-benefit policies to changes of the income situation of the household — only cushioned the negative impact of the crisis to a limited extent and mostly at the top of the distribution.

With the COVID-19 crisis protracting and likely worsening, maintaining and expanding social protection programmes will be key to avoid more households falling into poverty

In the long run, supporting the growth of the formal sector will enhance society’s resilience in future crises and provide faster crisis response than discretionary measures

Frequently collected, high-quality survey data are crucial to improve the understanding of the impact of tax-benefit policies for poverty and inequality in general and during crises

This reflects the large informal sector of the Zambian economy with few people paying income tax and social security contributions as well as the design of social protection policies. Most benefits do not react to income changes but rely on fixed eligibility rules due to the difficulty of reliable and frequent income information for each household. Thus, existing benefits are not designed to increase coverage in response to a crisis situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Join the network

Join the network