Research Brief

Job duration in apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa

The two primary features of a job are its wage and how long it lasts. Today, there is an extensive literature on wages in the developing world thanks to the expansion of national household survey data. However, far less work has been conducted on job duration in these countries, primarily due to the intensive nature of data collection for job spell analysis. Understanding job duration is important for emerging markets in two key ways. First, the length of a given job relates directly to employment stability and worker vulnerability. Second, at a macro-level, job spells provide signals about dynamism and mobility in the labour market.

There has been little research so far comparing job duration in the Global South with that in the Global North. New data makes this analysis possible for South Africa

The main features of job duration in South Africa are similar to those in the developed world in that most new jobs end early, the hazard declines with tenure, and ‘lifetime’ tenure —tenure of 20 years or more — is common

In post-apartheid South Africa, half of new jobs survive for less than a year, which is about the same as in the United States in the mid-1990s, but shorter than in Germany during the same period

During apartheid long-term tenure did not necessarily signal labour market advantage for Black populations who were the target of segregationist policies at the time

The median length of current tenure lengthened over the post-apartheid as unemployment worsened, suggesting slacker hiring rates and a decline in the mobility of employees after the global financial crisis in 2007–08.

Two recently publicly-released datasets make it possible to study job spells in the South African context for the first time, and to analyse the duration of jobs both during and after apartheid.

The analysis indicates similarities between job spells in South Africa and those in the Global North: most new jobs end early, the job duration hazard declines with tenure, and lifetime tenure is common. However, without an understanding of the distortions caused by apartheid-era labour market and segregationist policies, results from that era could be misinterpreted.

Job duration in South Africa: similar characteristics to the developed world

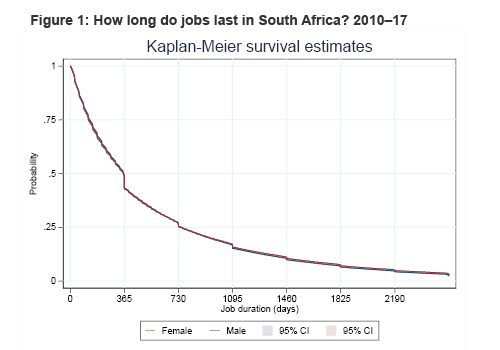

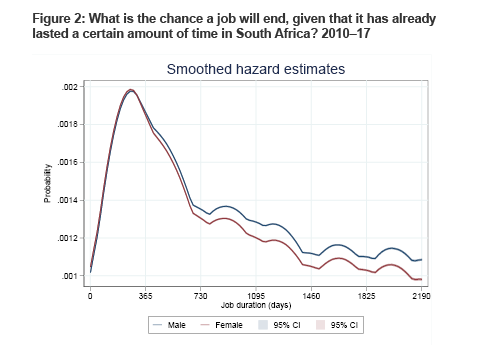

Figures 1 and 2 describe estimates of the job survivor and hazard functions using South African tax data for the period 2010–17. The survivor function is the chance a job will last a given amount of time and shows that half of jobs end within a year. This rate is about the same as in the US in the mid-1990s, but shorter than in Germany during the same period.

The hazard function on the other hand measures the chance a job will end, given that it has already lasted a given amount of time. The hazard function first increases and then steeply declines, peaking at about eight months. Jobs that have lasted about eight months are then most likely to end, but jobs that last longer are much less likely to end. For example, a job that has lasted four years (1,460 days) has a much lower chance of ending than one that has lasted eight months. This captures intuitive ideas about how returns to gaining on-the-job know-how and skills for both employers and employees reinforce the chance a job will continue to exist. The hazard peaked at about six months in the US in the mid-1990s.

The role of gender and race in lifetime tenure

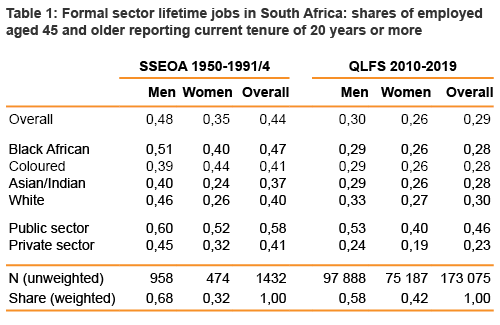

Long-term employment is common in post-apartheid South Africa and comparable to rates in developed countries: 31% of men and 27% of women over the age of 46 reported they had currently been in their job for 20 years or more between 2010–19.

During apartheid, Black Africans had a higher incidence of lifetime tenure than white South Africans. Black (Coloured and African) women in particular had very high levels of long-term tenure compared to white South African women. Generally-speaking, more lifetime tenure is viewed as an advantage. However in this case, higher lifetime tenure amongst Black and Coloured women was more likely driven by segregationist labour policy. During apartheid, Black South Africans were required to have extremely long tenure (e.g., 10–15 years) with a white employer to qualify for rights which enabled them to live in urban areas. These areas were better serviced by the state, and jobs were more numerous in cities than in the homelands.

After apartheid ended, freedom of movement was extended to all, relaxing the importance of long-term tenure for access to a better life and freeing women to expand their job search and take other factors important to them into consideration. This is most likely the reason for a decrease in the incidence of lifetime tenure amongst Black South Africans and women in particular.

A high incidence of lifetime tenure among Black populations during apartheid is likely indicative of restricted bargaining power, limited job opportunities, and other non-job-related considerations, rather than labour market advantage. On the other hand, lifetime tenure for white men remains high both during and after apartheid, with white men enjoying the highest rates of lifetime tenure in post-apartheid South Africa in coherence with their labour market advantage.

An exciting research agenda for labour dynamics in South Africa

This work represents a first step in investigating job duration in South Africa. More work is required to quantify job duration in detail in each dataset, as well as to carefully understand the data quality issues facing researchers in each regard. Beyond building this baseline, much remains to be learned about how job duration interacts with demographics, earnings, and on trajectories through the labour market in South Africa.

Join the network

Join the network