Blog

Local governance in Ghana is more complicated than central versus regional

Measuring the effectiveness of local government in Ghana is hampered by incomplete records, but despite that there are still visible patterns, write Daniel Chachu, Michael Danquah, and Rachel M. Gisselquist.

Decentralisation, or the transfer of power, responsibilities, and resources from central to subnational governments, is a hot button topic in Ghana. Critics raise concerns that decentralisation promotes political fragmentation, but proponents highlight opportunities to move government closer to the people, facilitating participation, improved public accountability, and the better delivery of public services.

Despite the debate, there is a lack of empirical data about whether central or subnational governments deliver better governance. There are various ways to measure the quality of governance at a national level. But on the subnational level, especially in developing countries where data quality and gaps have complicated measurement, this is much harder.

To complicate matters, it isn’t just a conversation about central versus local but about which subnational governments perform better than others, and why. Governance may be decentralised within the state or province or disseminated to lower levels such as the district or municipality. There are also different mixes of administrative, fiscal, and political responsibilities to consider when evaluating which model works best.

Making democracy work in Ghana

There are dozens of ways to measure local governance. For example, to measure legislative innovation, you can track the time it takes for a model by-law to be picked up and passed by a district assembly. As a measure of local government stability and performance, you can count the average share of district assembly members who participate in meetings during a particular year. Or you could look at the ability of local government to raise its own revenues for development projects.

Since 1988, metropolitan, municipal, and district assemblies (MMDAs) in Ghana have operated under the direct policy supervision of the Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development. Over time, the number of MMDAs has increased from 65 in 1988 to 261 in 2023. Heads of MMDAs are appointed by the President but subject to the approval of a two-thirds majority of the members of local assemblies, most of whom are elected (30 per cent of the members are appointed by the President in consultation with local stakeholders). Despite this, local elections are supposed to be apolitical and political parties are barred from any form of involvement. Local governments hold a variety of political and administrative responsibilities and have a mandate to deliver local economic development. Large metropolitan assemblies generate significant funds locally through licenses, fees, taxes and other charges, but funding for most MMDAs is provided by the central government.

Local government at work

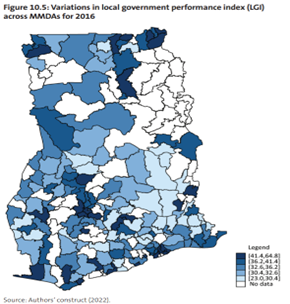

In Ghana, local governments in urban areas, and in southern Ghana, generally perform better. This is likely due to their proximity to the country’s economic and political centres. They are better able to mobilise revenue and are less dependent on transfers from the central government. Among the best performing districts, three large urban assemblies top the list based on their political process, internal operations and policy implementation: Kumasi Metropolitan, the administrative capital of the Ashanti Region and historically Ghana’s second largest city; Accra Metropolitan and Adentan Municipal, both part of the Greater Accra capital region.

Despite their better overall performance, there is greater variability among urban MMDAs than rural MMDAs. For instance, the top performers include Pusiga, a rural district, located near the northern border with Burkina Faso, and Jirapa, in the northwest. This suggests that measures of performance that focus solely on the delivery of outputs and outcomes may be missing out on important aspects of the policy processes, for example, administrative capacity that may be relevant to securing robust local economic development.

Figure: Variations in local government performance index (LGI) across MMDAs (Ghana, 2016)

Variations in local government performance

In addition, poverty tends to be lower in districts with higher local government performance scores, for example in Kumasi Metropolitan, Accra Metropolitan and Adentan Muncipal. The local government scores tend to correlate well with Ghana’s ‘District League Table’, a measure of local development initially developed by civil society organisations and currently being used by the National Development Planning Commission as a monitoring tool to track progress at the subnational level.

A variety of factors are surely at work here, but these relationships are consistent with our expectation that more effective and responsive local governments are better able to support well-being in their areas.

Decentralisation alone does not guarantee improved public accountability or better delivery of public services. There is a lot of variation in the quality of governance across Ghanaian districts and a better understanding of why can help in efforts to support better local governance.

This blog is based on a chapter in the book Decentralised Governance published by LSE Press.

Daniel Chachu holds a PhD in Development Economics from a collaborative PhD Programme between the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER) based in Helsinki, Finland and the University of Ghana. His research interests are broadly situated within the field of Political Economy and are at the intersection of Natural Resource Economics, Institutional Economics and Public Economics.

Michael Danquah is a development economist and Research Fellow at UNU-WIDER. He currently co-leads the projects Transforming informal work and livelihoods, Sub-national institutional performance across Ghana’s districts and regions – variation and causes, and Structural Transformation in African cities.

Rachel M. Gisselquist is a Senior Research Fellow with the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). She works on the politics of developing countries, with particular attention to inequality, ethnic politics, statebuilding and governance and the role of aid therein, democracy and democratization, and sub-Saharan African politics.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network