Blog

Climate resilient development needs effective co-operation

The rise of resilience policy in sustainable development

Climate resilience is an increasingly popular response to development in a time of polycrisis or permacrisis. From the IPCC to the OECD, World Bank, and UNDP, the core notion of 'resilience' counters radical uncertainty and social-ecological risks. The COVID-19 pandemic offers but another example in an array of human and natural disasters. As such, resilience counters shared climate risks that jeopardize development prospects around the world.

Resilience policy narratives thus open a valuable channel for sustainable development and climate action. However, given the diverse stakeholders and interests involved, how exactly does resilience apply across development contexts—and what are the implications for effective co-operation?

Table 1: A small sample of the many flavours of resilience in sustainable development

From a resilience paradigm to a resilience consensus

Contrary to talk of a resilience paradigm, recent findings from development studies suggest the lack of a coherent paradigm at all. Instead, resilience acts like a development buzzword with potentially harmful effects. On one hand, definitions of resilience evidence a common starting point: an ability to bounce back—or even bounce forward—from stressors and shocks. However, ensuing meanings and measures of resilience are as diverse as the meanings and measures of development itself.

What instead emerges is a resilience consensus in sustainable development. This raises the possibility of both helpful and harmful outcomes in resilience’s rallying call and siren song.

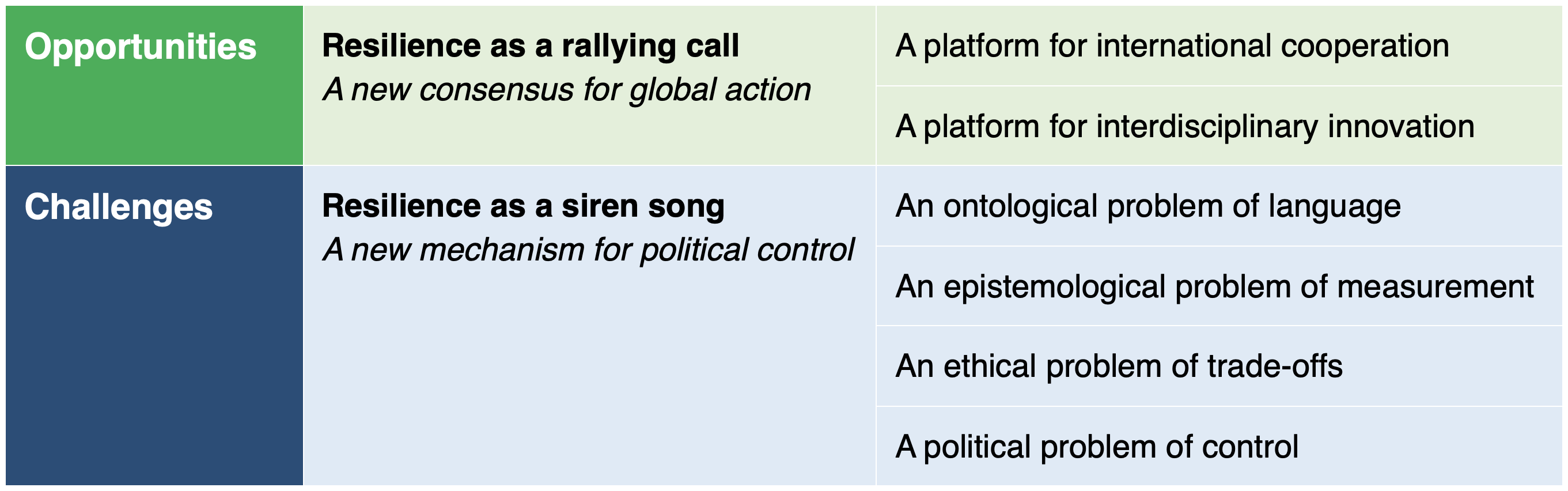

Resilience as a rallying call and siren song

Table 2: Opportunities and challenges of a resilience consensus in sustainable development

As a rallying call, resilience expands recognition of the complex risks posed by climate change on all countries and peoples of the world. This includes recognition of the need to address the complex interplay between the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—in addition to sustainable development's three dimensions (social, economic, and environmental). Correspondingly, this resilience consensus offers a compelling path for SDG 17 to build partnerships for the goals.

This resilience consensus is vital in a time of rising geopolitical tempers and global temperatures. Climate change is not just a problem of science, but also a problem of politics. Even a shallow consensus adds grounds for collective action; lest geopolitical divisions lead to a global tragedy of the commons.

As a siren song, however, lack of communication and transparency can lead to tragic outcomes. These range from latent semantic conflicts and moral dilemmas to hazards of political coercion—all operating under the cover of resilience. A conservative emphasis on bouncing back (versus bouncing forward) may hinder green transitions. Even when geared towards structural transformation, resilience policies may produce winners and losers; for example, between competing economic sectors or between multiple social-ecological scales (e.g., local, national, and global).

At best, stakeholders risk talking past each another instead of to one another in pursuit of resilience. At worst, uncritical adoption of resilience narratives can enable co-option and coercion. Here, resilience can spell the return of an older Washington Consensus repackaged anew. What, then, can the development scholar or policymaker do with resilience?

Resilience and the effectiveness principles

The challenge here is to acknowledge resilience policy's potential for harm/help without falling into blind optimism nor cynicism. In this regard, the effectiveness principles offer a possible solution. Supported by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC), these encompass country ownership, focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and transparency and mutual accountability.

Resilience requires all four effectiveness principles to enhance climate action and sustainable development. For example, inclusive ownership, transparency, and accountability are key to the social cohesion and trust needed to bounce back (or bounce forward) from catastrophic risks.

Like the very idea of development, resilience requires critical oversight. This entails recognizing its inherent potential for harmful outcomes. Who gets to define and measure resilience for whom? To what extent does resilience (dis)incentivize inclusive participation and structural transformation?

This politics of resilience policy adds important directions for future work. As seen in COP27 and the upcoming COP28, resilience continues its relevance as part of a just transition towards clean energy and climate-resilient futures. In upholding ownership, inclusivity, results, and accountability, the GPEDC effectiveness principles add further means of navigating resilience's hidden hazards to deliver on its promise for sustainable development and global climate action.

The content of this blog article is based on the findings of the working paper Building resilience knowledge for sustainable development: Insights from development studies.

This post was originally published by the Global Partnership. Read the original here.

Dr. Albert Sanghoon Park is Lecturer at the Department of International Development at the University of Oxford.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network