Blog

Sub-Saharan Africa had a manufacturing renaissance in 2010s – it’s a promising sign for the years ahead

The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on the global economy, with world output contracting at 3.5% in 2020, and no recovery likely before the fourth quarter of 2021. Similar to other developing regions, sub-Saharan Africa recorded a 2.6% decline, following strong growth of 3.2% in 2019.

Unfortunately, this comes at a time when the region has been experiencing a surprising and very welcome manufacturing renaissance. Historically, industrialisation has been associated with rapid technological improvements and sustained growth in the western world, and more recently east Asia, gainfully employing millions of workers and helping it to close the income gap with richer countries.

Until the 2000s, sub-Saharan Africa was actually de-industrialising: the mood was gloomy as the little manufacturing activity that did exist was disappearing, and with it the traditional route to development and poverty reduction. In northern Nigeria’s biggest city, Kano, for example, textile factories, leather tanneries and ceramics plants were visibly falling into disrepair. There were reports of empty industrial parks in Ethiopia, while South Africa’s footwear industry had collapsed.

But recently the trend has reversed across the region. We have documented this in new research based on an in-depth investigation of national statistics in 51 countries, including 18 in sub-Saharan Africa, ranging from South Africa to Ethiopia to Nigeria to Kenya to Mauritius. These 18 countries account for nearly three-quarters of the GDP of the region, so they are a good representation of the overall picture.

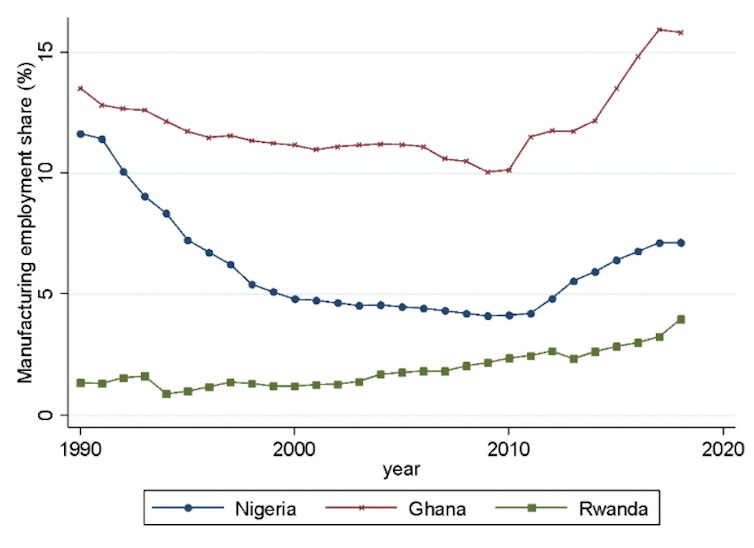

The graph below shows how this industrial renaissance affected the share of manufacturing employment in three of the countries in the study, namely Nigeria, Ghana and Rwanda. Manufacturing in Ghana and Nigeria started to expand from around 2010 onwards, while in Rwanda it had been steadily increasing as a share of employment since the 2000s. Rwanda’s industrialisation includes the opening of its first car assembly plant by Volkswagen in 2018, for instance.

Manufacturing as a % of employment, 1990–2018

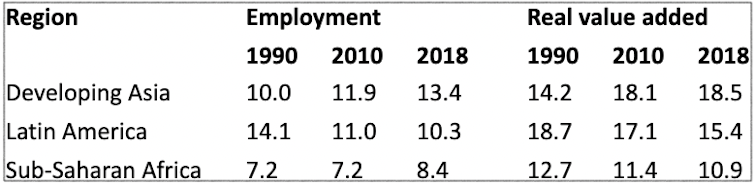

We saw the same broad trends across the region, although in some – such as Mauritius – industrial capacity continued to decline. As you can see from the table below, the average percentage of employment in manufacturing in the African countries in our study remained static at 7.2% between 1990 and 2010 but had risen to 8.4% by 2018. This is still low in comparison with developing Asia and Latin America, but the trend is clear enough.

Manufacturing in Africa, Latin America and east Asia

Despite this promising trend, another thing to note from the table is that the manufacturing in the region as a share of real value added (in other words GDP) actually decreased. What this tells us is that productivity growth in manufacturing was lower than in the economy as a whole. In fact, manufacturing productivity barely improved at all in the region in the 2010s.

To explain why manufacturing employment rose while productivity stayed the same, we need to make a distinction between small and large firms. Large modern firms tend to be more productive than smaller firms, partly because they benefit from economies of scale so that more goods can be produced on a larger scale but with lower input costs.

What seems to have been happening is that smaller firms have been mainly responsible for sub-Saharan Africa’s industrial resurgence, hiring workers to make more low-quality goods such as processed food, clothing and wood products to meet rising demand from domestic consumers. This is different to manufacturing in east Asia, which was driven by exports. In sub-Saharan Africa, some manufacturing work moved from China to countries such as Ethiopia in search of lower wages, but it’s debatable to what extent this has driven the overall trend towards increased industrialisation.

The pandemic effect

One major question that stems from our research is how this trend towards more industrialisation in sub-Saharan Africa is likely to have been affected by COVID-19. Various economic activities have taken a hit, particularly travel and tourism, as lockdown policies have put a break on commerce and travelling. Fundamental drivers of long-term manufacturing growth have also been held back – especially education, with schools closed in many countries for extended periods.

On the other hand, since the recent manufacturing growth has mainly been serving a domestic and not an export market, it is at least not primarily depending on demand from other countries. But as far as exports are concerned, the initial indications are that commodity exports in sub-Saharan Africa were hit harder than manufacturing – vividly illustrated by the collapse in oil prices in 2020 (which has since bounced back). The recently created African Continental Free Trade Area might also boost regional trade in manufactured goods in the years to come. So all in all, the manufacturing renaissance in the region may be relatively resilient.

As Arthur Lewis, a Nobel-prize winning economist from St Lucia, noted back in 1979, expanding small-scale activity in manufacturing is an important part of the development process. In sub-Saharan Africa, this has been made possible by an expanding market for domestic produce. Assuming the pandemic has not undermined this too badly, there is no reason why this trend should not continue in the decade to come.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network