Blog

Realizing socioeconomic rights with a limited budget

The South African constitution is considered progressive and transformative in intention due to its inclusion of socioeconomic rights, such as the right to education, food, and healthcare. However, some of these rights are qualified by the availability of state resources, which places an imperative on government to realize these rights progressively as resources become available.

The South African constitution is considered progressive and transformative in intention due to its inclusion of socioeconomic rights, such as the right to education, food, and healthcare. However, some of these rights are qualified by the availability of state resources, which places an imperative on government to realize these rights progressively as resources become available. The deteriorating economy, low economic growth, and worsening public finances have led to increasing pressure on the government to cut its expenditure to regain fiscal sustainability and stem the growth of its debt burden. This threatens to roll back the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights, a phenomenon known as retrogression. So how should government reconcile the imperative placed on it by the constitution to realize socioeconomic rights with its limited and shrinking resources?

The South African constitution includes a number of socioeconomic rights, such as the right to education and access to housing, food, and healthcare. Nevertheless, the constitution qualifies some of the socioeconomic rights by the availability of resources to the state. This places the imperative on the state to realize these rights progressively, as resources become available.

With the deterioration of the South African economy and public finances, there is increasing pressure on government to cut its expenditure to regain fiscal sustainability and stem the growth of its debt burden. The situation has become starker in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic deterioration and the steps taken to stabilise the government’s debt burden threaten to be retrogressive and thus roll back the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights. The possible retrogression of rights has led a range of individuals and non-governmental organizations to oppose the cut-back of expenditure.This raises the question, addressed in this article, of how the government should reconcile the imperative placed on it by the constitution to realize socioeconomic rights with the limited and even shrinking resources available to do so. The need for such reconciliation lies in the constitution, which also places an imperative on government to manage its debt.

Limited resources and the realization of socioeconomic rights

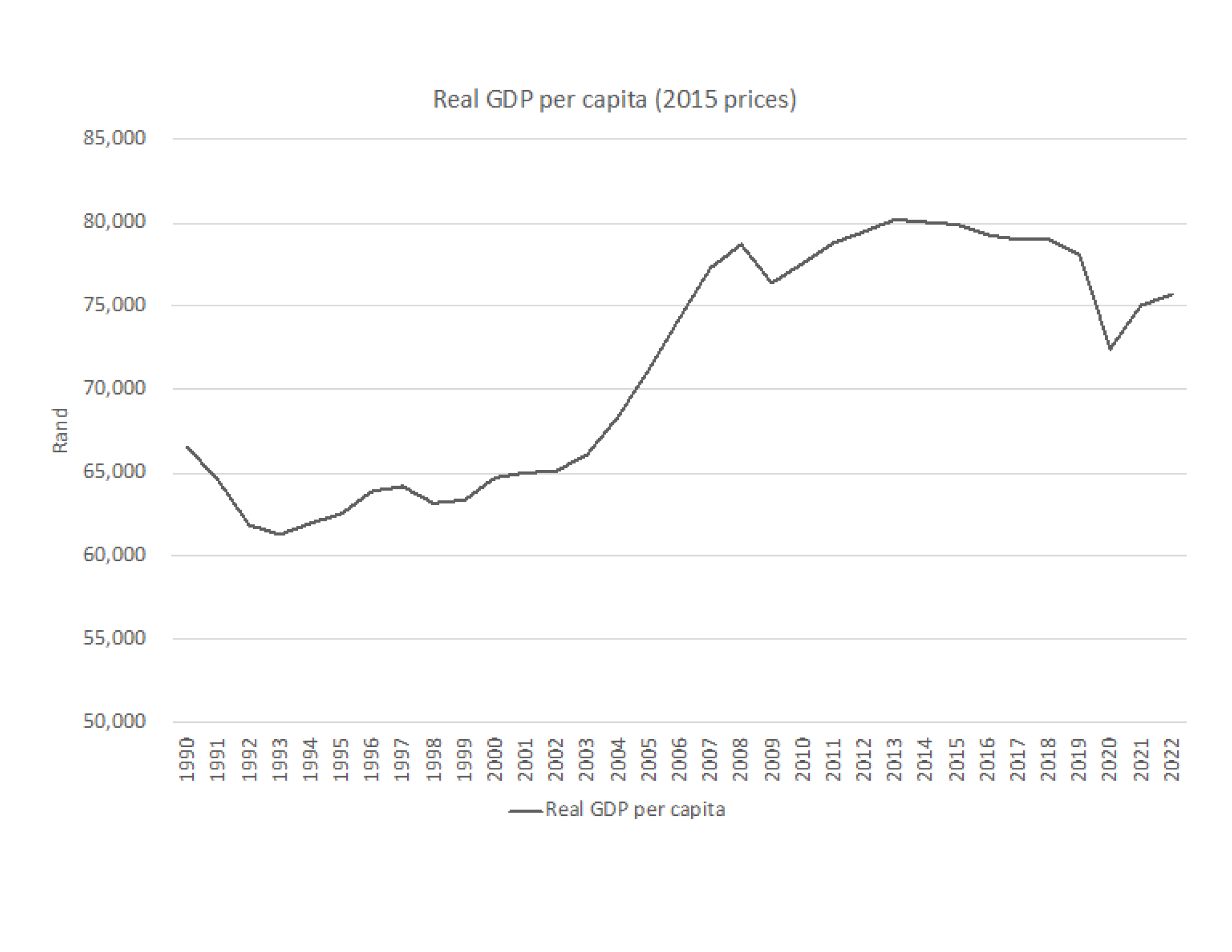

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic caused the collapse of economic growth and a steep increase in unemployment, poverty, and hunger, the South African economy was in trouble. Since 2014, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita had been declining (see Figure 1) and by 2022 it was only slightly higher than it was in 1981. This resulted from a drop in the real GDP growth rate, which has been declining since the late 2000s (see Figure 2).

The unemployment rate has been rising since 2015, with the official and expanded unemployment rates reaching 32.6% and 42.1% in the second quarter of 2023, after improving slightly following the passing of the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 3). Government finances were also on an unsustainable path, with the debt-to-GDP ratio increasing from a mere 23.6% of GDP in the first quarter of 2009 to 72.2% of GDP in the second quarter of 2023 (see Figure 4). The deterioration of government finances led to steps to arrest the increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio. These steps, which include reining in expenditure growth, have not yet been successful in stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio. But cutting expenditure also may imply spending less on the realization of socioeconomic rights, resulting in the retrogression of these rights.

Figure 1: Real GDP per capita (2015 prices)

Figure 2: Real GDP growth

Figure 3: Unemployment rate

Figure 4: Total gross loan debt as % of GDP

Weak economic growth, the budget, and the constitution’s Whig problem

By saying in the constitution that we ‘progressively realize’ socioeconomic rights, we implicitly assume a Whig interpretation of history, assuming that (on average) we will experience an ever-improving human condition and that the future is, in general, always better than the past. An ever-improving human condition allows for progressive improvement of socioeconomic conditions and therefore the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights. But what happens when years of negative per capita economic growth (exacerbated by the economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis) shrink the available pool of resources? Do we roll back socioeconomic rights? It is precisely this prospect that spurred several social activists and public commentators to oppose budgetary cutbacks, and in some cases, even to call for increased expenditure as well as the rollout of a universal basic income grant.1

However, not all agree. Former Constitutional Court Justice Albie Sachs (2021) argues that under exceptional circumstances it is justified to temporarily cut back on expenditure related to the realization of socioeconomic rights. However, he argues that such cutbacks need to be justified by a set of criteria and be temporary in nature.

What are the criteria to decide on cutbacks?

A reduction in economic activity may be temporary, for instance during an economic recession, or result from a lower trajectory of the long-run trend at which output grows. When faced by lower revenue collections resulting in a larger deficit, the government will incur more debt. It will have to manage this debt; indeed, the constitution requires the government to effectively manage ‘the economy, debt and the public sector’.2

This includes ensuring that the government’s debt burden does not become unsustainable, resulting in a debt trap. However, managing ‘...the economy, debt and the public sector’ implies that the choice is more complex than just keeping the debt-to-GDP ratio low. And mentioning the economy, debt, and the public sector in one sentence also indicates that the constitutional framers understood the close link between them. Note also that expenditure by the public sector is responsible for the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights, which means that Section 215(1) implicitly links it to the management of the economy and debt.

If the reduction in GDP is cyclical or the result of a crisis such as Covid-19, the higher debt burden may itself be temporary. Governments typically implement countercyclical and counter-crisis macroeconomic policies, meaning they allow the budget deficit-to-GDP and public debt-to-GDP ratios to increase during recessions and crises, and reduce the ratios during economic upswings. With reasonable fiscal space available, a typical recession and crisis would not justify the retrogression of socioeconomic rights. Indeed, the countercyclical nature of the budget would be the mechanism protecting socioeconomic rights from retrogression.

However, retrogression becomes more of an issue in the face of slower GDP trend growth. When the per capita trend growth of the economy turns negative, as it has in South Africa since 2015, government revenue collection may be on a lower and flatter, even negative, real trajectory. In the absence of an adjustment in the level and trajectory of expenditure growth, the debt burden will likely be on an unsustainable, upward trajectory. Increasing tax rates and decreasing expenditure, including on socioeconomic rights, are the two options open to government to arrest this upward trend. Over time, of course, the aspiration is to return trend growth to positive territory, so that over the long haul the government can return to making progress in the realization of socioeconomic rights.

The pace of retrogression and long-term rebound

In an effort to protect socioeconomic rights while policy makers try to reverse the negative trend in long-term output, retrogression should, where possible, be undertaken at a slower rate than the rate at which per capita output is shrinking. Care should also be taken to use the right metric when considering the extent to which socioeconomic rights are rolled back. For instance, it is possible to reduce health expenditure in real terms by granting lower-than-inflation salary increases to doctors, while not reducing the number of doctors and therefore not eroding health-related rights. However, if the number of doctors or hospital beds per 1000 people fall, there is retrogression.

The intergenerational dimension

The choices that government face become even more difficult in an intergenerational context. In the face of shrinking resources and a rising debt burden, government may face a choice between a more limited reduction in the welfare of the present generation versus improving the welfare of the future generation. The latter requires accepting a relatively larger reduction in the welfare of the present generation (e.g. lower grants or a lower level of health care), thereby using the freed-up resources to improve the welfare of future generations, possibly by investment and growing the economy. Establishing whether such economic growth can be inclusive, form part of an assessment of the trade-off.

This recalls the Brundtland Commission’s definition of sustainable development, which laid the foundation for the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals: ‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.3

The policy imperative in this definition is the improvement of the welfare of the present generation without negatively affecting that of future generations. In other words, we should heed Herbert Hoover’s sarcastic warning ‘Blessed are the young for they shall inherit the national debt’.4 We should not live at the expense of future generations, leaving them the cost of servicing the debt incurred by the current generation.

A variation on the Brundtland Commission’s definition is the choice between improving the welfare of the present generation versus improving the welfare of future generations. If we have a rand to spend, do we spend it on a higher social wage for the current generation (e.g., grants, housing) or do we invest it in capital goods, infrastructure, and education to improve the lives of future generations? Unlike the Brundtland Commission’s definition, which considers those cases where a rand spent today harms future generations, the variation is less harmful: spending the rand today to benefit the current generation does not harm the future generation, while investing it might benefit the future generation (but then, of course, the current generation does not benefit).

Towards true sustainability: four pillars of indicators

Maximizing the intertemporal realization of socioeconomic rights involves four dimensions (Figure 5), each with its own set of indicators:

- the progressiveness with which socioeconomic rights are realized at any given point in time,

- the sustainability of fiscal policy,

- the level and sustainability of economic growth, and

- the inclusivity of economic growth.

Figure 5: The four dimensions to maximize the intertemporal realization of socioeconomic rights

Judging whether the government maximizes the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights intertemporally and sustainably requires consideration of all four of these dimensions. In the event of a crisis or a downward trend in per capita GDP that threaten revenue collection, indicators for all four dimensions will also serve as a tool to use when the government minimizes the extent of retrogression.

Under ideal conditions, per capita income grows, shrinking the income and wealth gap and generating higher tax revenue, which in turn allows for (i) the progressive realization of socioeconomic rights, (ii) maintaining a sustainable debt burden, and (iii) financing further growth-enhancing investment in physical and human capital. However, if trend growth falters, growth cannot be inclusive (simply put, if there is no growth, there is nothing to be inclusive about). Faltering trend growth may also result in a continually rising debt-to-GDP ratio. This may require a temporary implementation of retrogressive measures with respect to socioeconomic rights until such time as positive per capita trend economic growth is restored and the debt-to-GDP ratio is at a level where its interest cost does not excessively crowd out other (social) expenditure items in the budget.

Restoring economic growth will probably also require a package of fiscal and regulatory measures to stimulate the economy. Higher economic growth will restore the sustainability of both development and fiscal policy. Indeed, development cannot be sustainable unless fiscal policy is sustainable, and vice versa.5

Phillipe Berger is Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at UNU-WIDER.

This article is republished from Econ3X3 under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

This article is based on a Southern Africa Towards Inclusive Economic Development (SA-TIED) programme paper titled 'The Economic Context of Realizing Socioeconomic Rights in South Africa.' SA-TIED is an initiative by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). The paper can be found here: https://go.unu.edu/lwUZQ

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

1 See Coleman 2020, 2022; Coleman et al. 2021; Dolley et al. 2023; ENCA 2020; Gqubule 2023; GroundUp 2020a, 2020b; ICESCR 2019; Masson 2023).

2 Republic of South Africa 1996: Section 215(1).

3 World Commission on Environment and Development 1987.

4 Wolla and Frerking 2019

5 Burger and Calitz 2015

Join the network

Join the network