Blog

Adding insult to injury – the impacts of COVID-19 on urban youth in Mozambique

The negative economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mozambique range from reduced social interaction to business closures, job losses, and increased poverty. Existing evidence already shows significant effects on the transitions of young people graduating from technical and vocational schools into the world of work. For disadvantaged youth in urban areas, the pandemic has further reduced their prospects.

Data collected recently for the ‘Inclusive growth in Mozambique’ programme demonstrates that the pandemic aggravated already dire conditions and financial constraints for 22 and 23-year-olds in Beira and Maputo, the two largest cities in the country. The struggles of these urban youth are reflected in their low enrolment rates in higher education found in the data.

Only one third accessed education despite higher aspirations

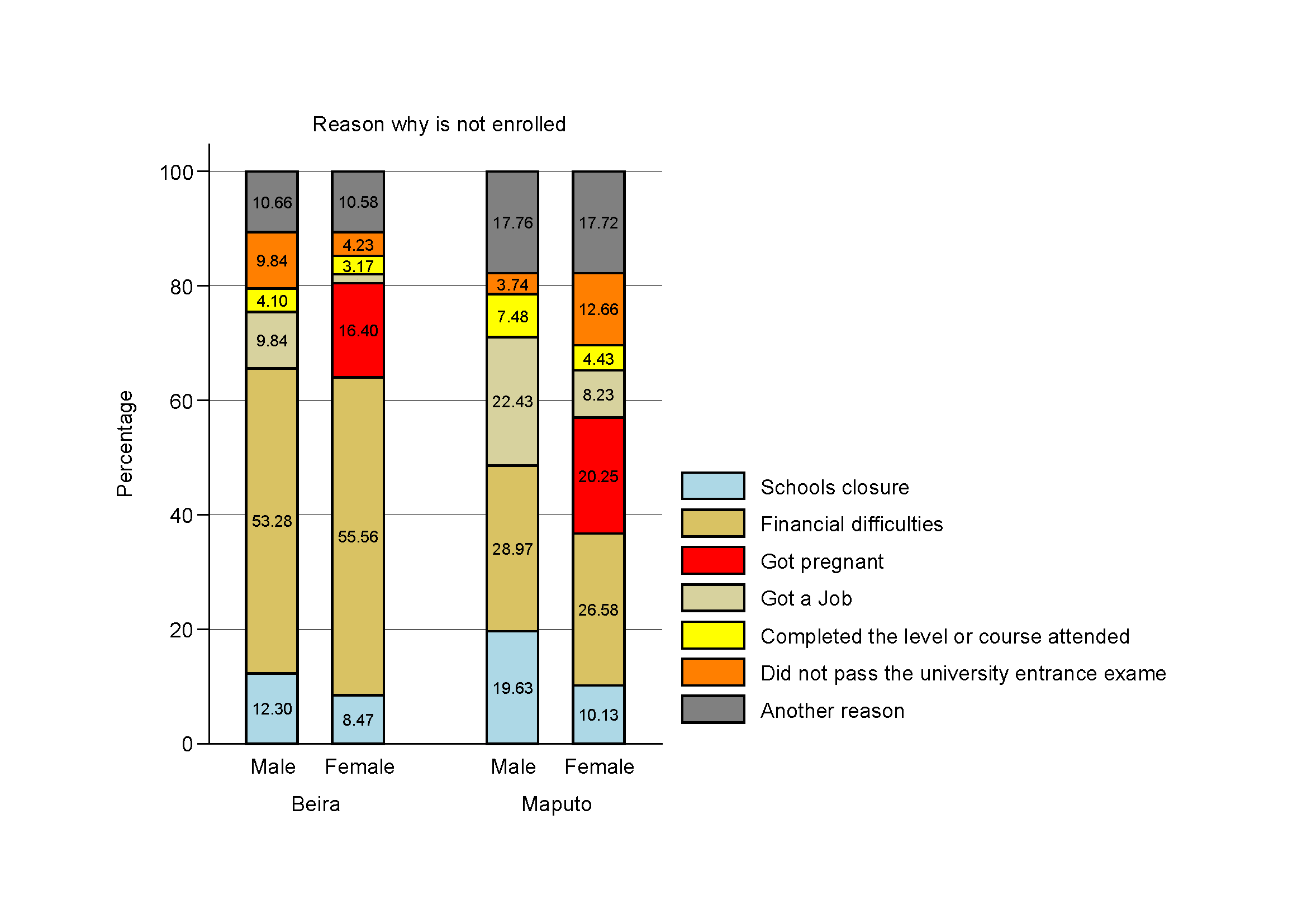

Even though roughly three-quarters aspire to a higher education, only one-third are enrolled. School closures, which are the direct result of the pandemic, have reduced access to education but these are not the primary obstacle. As the figure below demonstrates, school closures only account for between 9–20% of the reasons cited by the unenrolled.

Table 1: Education levels and aspirations

| Highest level enrolled or concluded | Male (%) | Female (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic literacy | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Primary school | 7.4 | 15.6 | 11.9 |

| High school | 68.1 | 69.4 | 68.8 |

| Technical education | 8.3 | 7.1 | 7.7 |

| University education | 16.3 | 7.7 | 11.5 |

| Enrollment | |||

| Temporarily stopped | 61.2 | 70 | 66.1 |

| Enrolled | 38.8 | 30 | 33.9 |

| Highest education level aspired | |||

| Primary school | 0.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| High school | 12.8 | 16.4 | 14.8 |

| Technical education | 9.8 | 11 | 10.5 |

| University education | 77 | 70.3 | 73.3 |

Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the MUVA Urban Poverty Survey

The primary reason is financial difficulties, especially for respondents in Beira. These are related to the important role many youth play as active contributors to the household income of their families. As their own financial situation, and that of their families, has become more pronounced by the COVID-19 pandemic, access to education has narrowed. Related to this, for young men in Maputo getting a job was the second reason they stopped pursuing their education.

There are also important gender differences in these constraints. For young men, the need to enter the labour market may disrupt their education. For young women, pregnancy is also often a disruptor of educational aspirations.

Figure 1: Reason for not being enrolled in education

Urban youth play an important role in household income

To understand better how young people and their families have coped, we look at youth contributions to household income, saving behaviour, and credit access (Table 2). Around 80% of employed respondents (around one-third of the total) contribute to their household’s income. Many contribute more than half of their salaries. Their employment plays an important role in household consumption and therefore families’ capacity to cope with the COVID-19 crisis.

Savings and access to credit are also important for coping. Many youth are able to save some of their income. Although the propensity to save is higher for women, access to credit is higher for men. Overall, slightly more than half of the young people report access to credit. It should also be noted that credit access is higher for the employed (65%) than for the unemployed or self-employed (57%).

Table 2: Contribution to household income from salary

| Maputo | Beira | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contribution to household income from salary | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Total |

| Do not contribute | 10.1 | 15.7 | 12.6 | 12 | 21.4 | 15.9 | 14.4 |

| Less than half | 58.5 | 58.3 | 58.4 | 54.3 | 47.6 | 51.6 | 54.6 |

| More than half | 23.3 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 26.4 | 24.1 | 25.5 | 23.8 |

| Almost everything | 8.2 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the MUVA Urban Poverty Survey

Employment levels mostly unaffected by COVID-19

It is widely agreed that COVID-19 has had a considerable impact on labour markets around the world. Nevertheless, for poorer youth in Mozambique’s major cities it seems the additional immediate negative impacts of COVID-19 on employment were not that strong. This would be a silver lining if the situation wasn’t already bad before the onset of COVID-19. Only around 29% of youth were employed before government restrictions were imposed. By the time of the survey, this had risen to 33%.

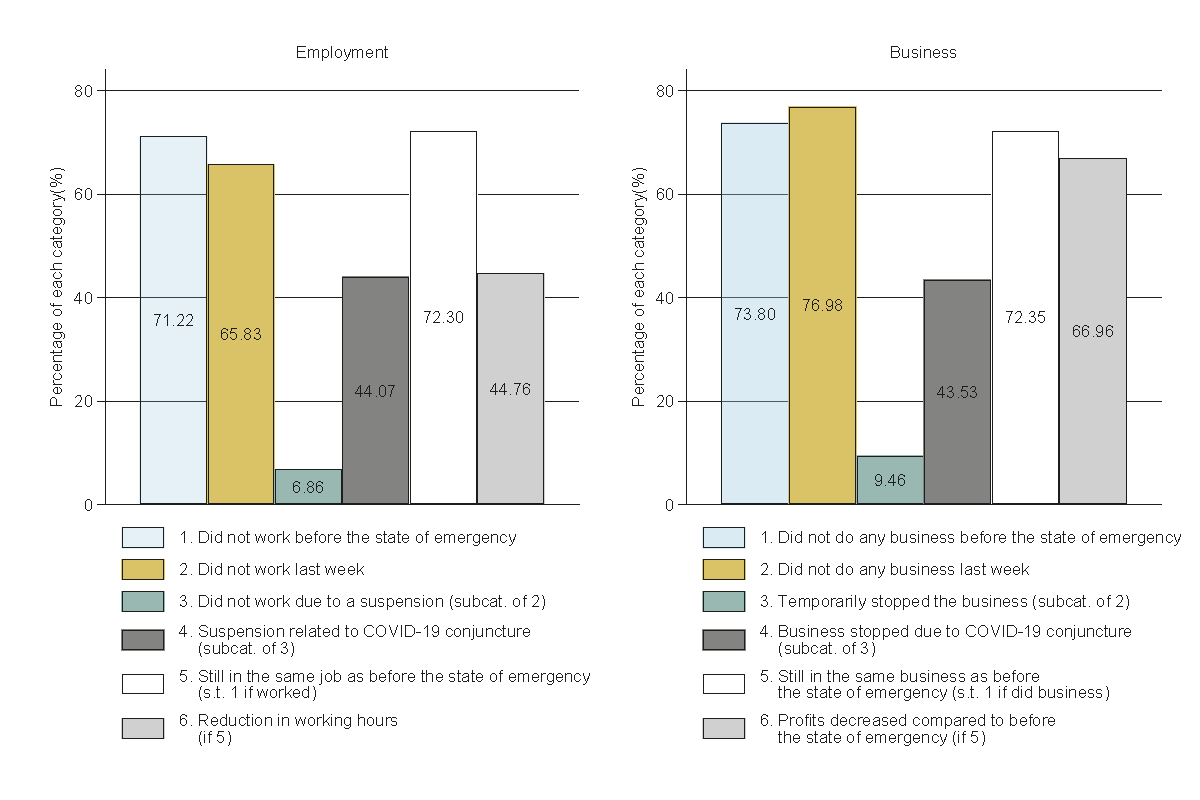

This gain in youth employment should be interpreted with caution as COVID-19 did cause job losses among those employed, even as it pushed previously unemployed youth into the labour market (see Figure 2). Additionally, of the few who were employed and did not change jobs (more than half) 45% experienced a reduction in their working hours. There are also concerns related to the quality of these jobs. Only a third of employed youth have formal contracts, while the majority work casually without any specific agreements.

Figure 2: Impact on employment and business

Youth stopped working in family businesses during the pandemic

The family business is often an alternative employer for young Mozambicans. A relatively high percentage of male respondents from Beira worked in family businesses. COVID-19 has negatively affected this segment as more than 80% of these left the family business they were working in.

A further 26% of the youth surveyed operated their own business before the pandemic. By the time of the survey, this percentage was reduced to 23%, evidence that some youth lost businesses. Two-thirds of those who remained open saw their profits decline.

Final considerations

The main takeaways from the survey data are that few young Mozambicans pursue education beyond secondary school, such as technical and vocational training and education (TVET) or university. This is mainly because they cannot afford to finance further studies, despite their aspirations to do so. These constraints existed before the pandemic but were aggravated during the crisis. Considering that a majority of youth were unemployed throughout and that employed youth contribute to household income, high levels of youth unemployment have increased household vulnerabilities.

Policy makers should therefore support young Mozambicans through opportunities to access financial resources to pay for higher education and to enter the job market. Altogether, it seems fair to say that although the pandemic negatively impacted the youth of Maputo and Beira, their situation was already dire before the crisis hit.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Eva-Maria Egger is Research Fellow at UNU-WIDER, Ivan Manhique is a Research Assistant with the Inclusive growth in Mozambique programme, and Finn Tarp is Professor of Development Economics and Coordinator of the Development Economics Research Group (DERG) at the University of Copenhagen. This blog is based on a survey carried out as part of the Inclusive Growth in Mozambique programme.

Join the network

Join the network