Blog

Who gets to work from home?

A suddenly relevant indicator of privilege and inequality in labour market outcomes

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes an unprecedented shock for labour markets around the world. Non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as social distancing, and limits on economic activity and mobility of people, are a necessary response. The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 80% of the world population is under some form of lockdown. All this makes working from home suddenly demanded and required.

In normal times, working from home is far from common, even in the most advanced OECD countries. According to the European Working Condition Survey (EWCS) data, the share of workers who work from home at least a few times a month ranges from about 10-15% — in Central Eastern, South Eastern, and Southern European countries, and Turkey — to 25-30% in the Nordic countries.

The incidence of working from home is strongly related to countries technological advancement. For example, higher levels of internet penetration usually mean a higher share of workers who work from home, at least from time to time. However, technology is not the only factor which matters. Cultural, managerial, and regulatory factors also play a role. This is illustrated, for instance, by the low incidence of working from home in Germany, which is noticeably below that of other countries at comparable levels of technology adoption.

Figure 1: The share of people who work from home is strongly related to countries' internet penetration

Source: author's calculations from the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey and World Development Indicators data.

It is quite possible that the pandemic will dismantle many cultural and managerial barriers, and that the incidence of working from home will increase rapidly and remain at higher levels even after the outbreak is controlled. The richer countries are, the more likely this is to happen.

In low- and middle-income countries, technological and infrastructural constraints will not disappear overnight. Slow connectivity, limits on data transfer, and substandard computers in households impede many people (who would otherwise be able to) from working from home. Firms that lack infrastructure for data sharing and managing remote work may struggle to catch up during the crisis and lose market share to more powerful firms. As a consequence, concentration of profits and incomes will presumably increase as the world of work goes online.

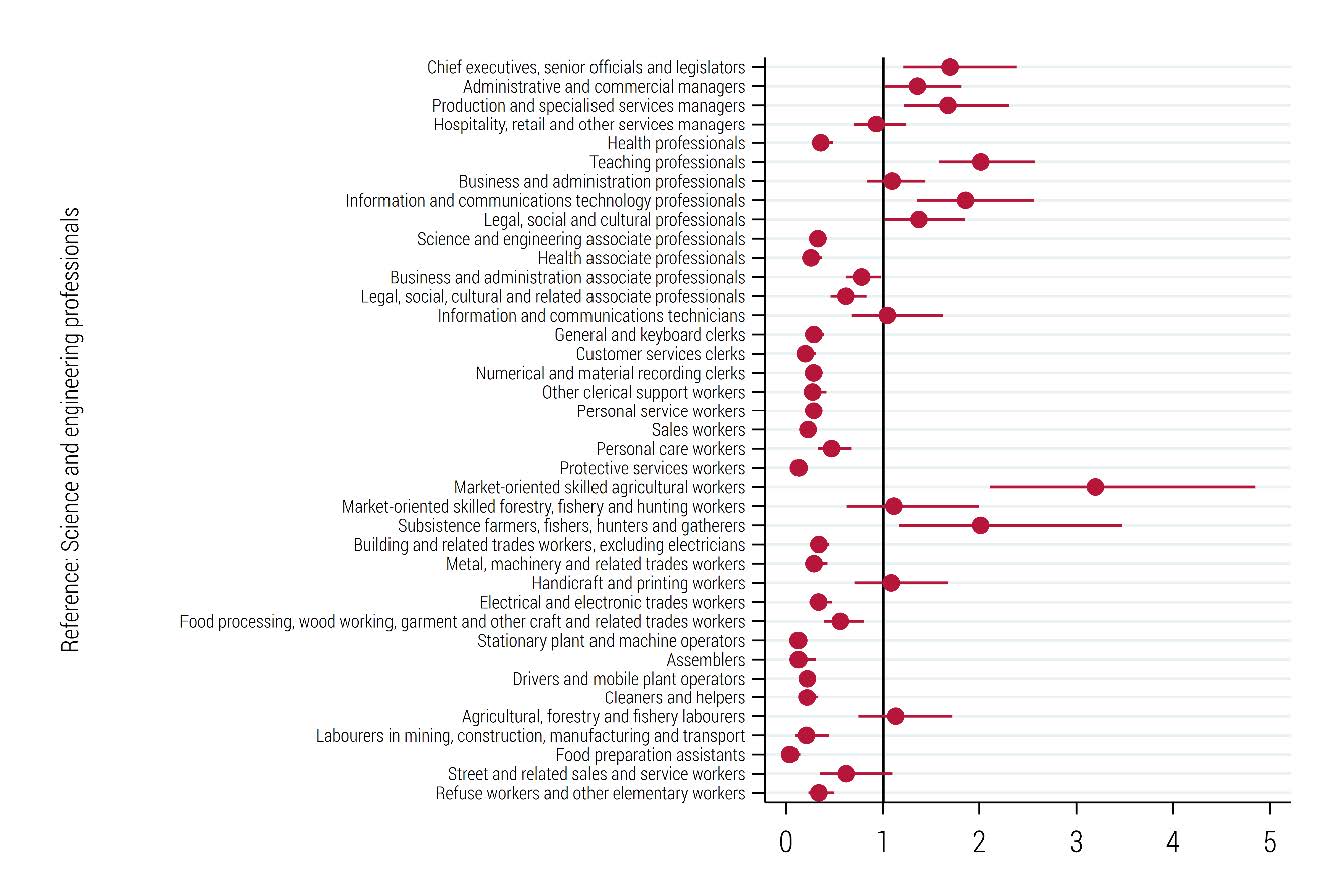

Moreover, some jobs simply cannot be performed from home. In Europe, workers in clerical occupations, sales workers, plant and machine operators, or assemblers, are about 80% less likely to work from home than managers. As a result, workers who are in a weaker position in labour markets are also less likely to be able to work from home. In particular, women are less likely than men to perform market work from home, although women spend more time on childcare and care in general, and perform most of the unpaid work in the household.

Workers with at least college education are about three times more likely to work from home than workers without college degrees. Young workers, especially those aged 15–24, have lower chances of working from home than prime-aged workers aged 35–44.

Figure 2. The probability of working from home in low- and middle-skilled occupations is lower than in high-skilled occupations.

Source: author's estimations based on the 2015 European Working Conditions Survey data.

During the pandemic, the disparities in ability to work from home will widen. Early evidence shows that workers in occupations in which the majority of positions require higher education are able to move swiftly from office-based work to home-based work, while for other occupations, working in a shop, store, hotel, or a plant is inherent to the nature of the jobs. The longer it takes to control the outbreak, the larger will be the joblessness risk among groups that are less likely to be able to work from home and the more acute will be the choices they have to make between staying at home or risking their health in order to make ends meet.

The COVID-19 pandemic induces a shift towards working from home which may have a long-term impact on the organization of work. But working from home is the privilege, mainly, of the highly educated and already well-paid workers. It is also most prevalent in the most advanced countries.

The urgent need to work from home will therefore exacerbate existing inequalities in labour market outcomes, both within and between countries. Governments should tackle the digital divide to enable as many people as possible to work remotely. They should negotiate with telecom companies to increase data limits and slash fees related to calls and transfers between networks. They can cooperate with NGOs to distribute computers to those in need.

But importantly, governments have to acknowledge that many jobs cannot be performed from home and that most of the workers in these jobs are vulnerable to income losses. Cash transfers are required to preserve livelihoods and to ensure that people stay safe until the health crisis subsides.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University, nor the programme/project donors.

Join the network

Join the network